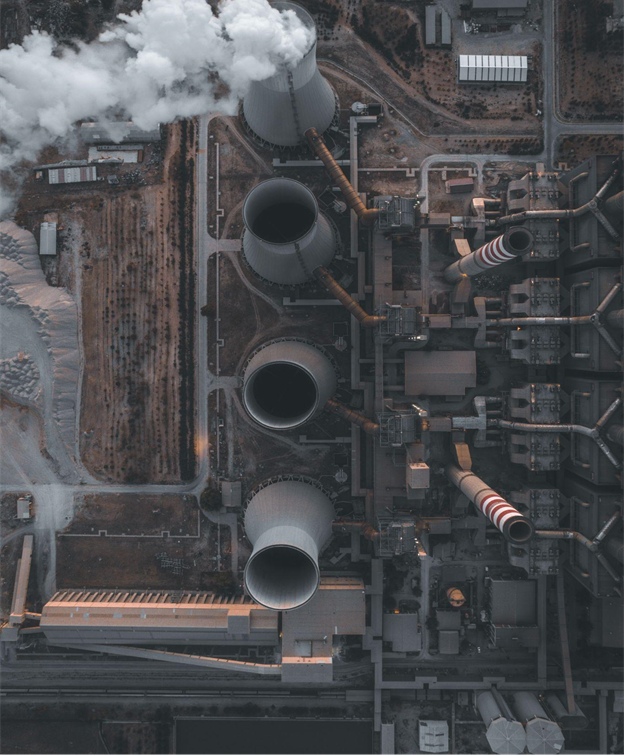

The Paris Climate Agreement and renewed commitments from the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26, have set the stage for a global industrial revolution. Industries that are currently reliant on fossil fuel-intensive energy systems are being incentivised and, in some cases, compelled to pivot towards cleaner and sustainable power sources.

The Paris Climate Agreement and renewed commitments from the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26, have set the stage for a global industrial revolution. Industries that are currently reliant on fossil fuel-intensive energy systems are being incentivised and, in some cases, compelled to pivot towards cleaner and sustainable power sources.

Technologies such as solar, wind and green hydrogen have been touted as the energies of the future. Solar PV and Wind have proven to be economically suitable alternatives to coal (one of the cheapest generation sources). The cost of utility-scale solar PV fell by 85% and wind (onshore and offshore) and 56% (onshore) and 48% (offshore), respectively, from 2010 to 2020. The International Renewable Energy Agency has reported auction prices for these technologies as low as USD 1.1 to 3 cents per kWh.

Despite all these successes, most renewables face the challenges of intermittency, storage and geographic limitations. For many developing countries, renewables are important for improving energy access but not for industrialisation. Therefore, it has become imperative for these countries to explore nuclear power as a clean and firm alternative. Pursuing nuclear does not necessarily relegate renewables to the backseat but instead presents the opportunity to diversify a country’s generation mix and increase the reliability of power supply for domestic and industrial applications.

WHY NUCLEAR?

Addressing the 470th Plenary Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on December 8, 1953, President of the United States of America Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered his “Atoms for Peace” speech; Eisenhower remarked that “….Experts would be mobilised to apply atomic energy to the needs of agriculture, medicine and other peaceful activities. A special purpose would be to provide abundant electrical energy in the power-starved areas of the world.”

This belief was affirmed by Ghana’s first President, Dr Kwame Nkrumah, in the 1960s at the inauguration ceremony of the Ghana Atomic Energy Project, where he also remarked that “we (Ghana) have therefore been compelled to enter the field of atomic energy because this already promises to yield the most economical source of power since the beginning of man. Our success in this field would enable us to solve the many-sided problems which face us in all the spheres of our development in Ghana and Africa.”

Years down the line, access to power remains a problem in Africa, with an access rate of just over 40 per cent and over 640 million Africans having no access to energy. African countries have not reaped the benefits of their numerous natural resources in part due to the low access rates and the relatively high cost of electricity on the continent.

HANDLING THE RISKS

Modern nuclear power plants are designed based on the “defence-in-depth” principle, which incorporates multiple safety systems in addition to the natural features of the reactor core. There are five (5) levels of protection that address issues such as prevention and management of malfunctioning and system failure, accident prevention and management, and limiting or preventing the release of radionuclides in the event of an incident. This is coupled with a strict regulatory environment in-country and from international watchdogs such as the IAEA. There is strict monitoring of nuclear power plant activities from employees down to the environment, making it difficult to cover up any “mess”.

There is also a lot of support from the international nuclear community to ensure continuous improvement of work practices and to provide capacity building for plant workers.

BUILDING A NUCLEAR POWER PLANT

Suffice to say that building a nuclear power plant is a fairly complicated process that involves complex designs, engineering and construction. The level of complexity is, however, dependent on the technology and vendor. On average, it takes between five to eight years to build one and costs are hard to estimate. The United Arab Emirate’s nuclear power plant which came with four reactors, developed by the state-owned Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation and the South Korea-based Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO), cost around $20 billion.

Some sources estimate that it would cost around $5 – $8 billion to construct a 1.1GW unit. Key activities which are undertaken include site selection, licensing, design, architecture, engineering, procurement, construction management, transportation and first fuel loading

The IAEA developed a milestones approach to guide newcomer countries on how to start a nuclear power programme. The approach addresses several infrastructure requirements for a successful nuclear power programme and guides the establishment of robust regulatory institutions. Nuclear power project financing can either be through public (government to government) or private financing. Multinational lenders such as the world bank and the IMF are not known to fund such projects. In Africa, the preferred choice for project financing would be through public financing, preferably with a vendor country open to flexible payment terms. However, a country could consider financing the project from their coffers with the right policies.

Egypt and South Africa are the leading nuclear power countries in Africa. Egypt has awarded a $25 billion contract to the Russian Nuclear Power vendor Rosatom for a 4.8GW power plant, and South Africa already owns and operates a nuclear power plant at Koeberg. Therefore, the Egyptian project is the most recent in Africa, and the project is being financed through a loan facility from the Russian government.

Ghana, Kenya, Algeria, Sudan, Tunisia, Nigeria, and Morocco are other African countries exploring nuclear power as an option.

CONCLUSION

Nuclear Power lies at the intersection of carbon neutrality and industrialisation; it is the subject of advanced energy research in many developed economies and will remain relevant for several years. African countries are more likely to reap the benefits of nuclear power now when the focus is on renewables instead of when it finally becomes mainstream, and there is competition for new nuclear builds. Already the European Union is considering including nuclear power in its green taxonomy, which begs the question, “will nuclear vendors be willing to build power plants in Africa when the European market is ripe for picking?”. The EU is a relatively stable market with bigger coffers to finance the new nuclear build, and it also has much to gain by switching to nuclear power, especially for energy and electricity independence. According to the European Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton, an estimated USD565 billion in investment will be required to decarbonise the EU’s energy sector with nuclear power plants. Amidst all the why’s and how’s, one thing is certain; for many African countries, the time to go nuclear is now or perhaps never.

Conflict Of Interest

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and they do not purport to reflect the policies, opinions, or views of the AfroScience Network platform.

Disclaimer

This article has not been submitted, published or featured in any formal publications, including books, journals, newspapers, magazines or websites.

Be the first to comment

Please login to comment